Article 13 – Constitutional Law Notes – Law Tribune

Introduction

Art. 13 : Laws inconsistent with or in derogation of the fundamental rights.-

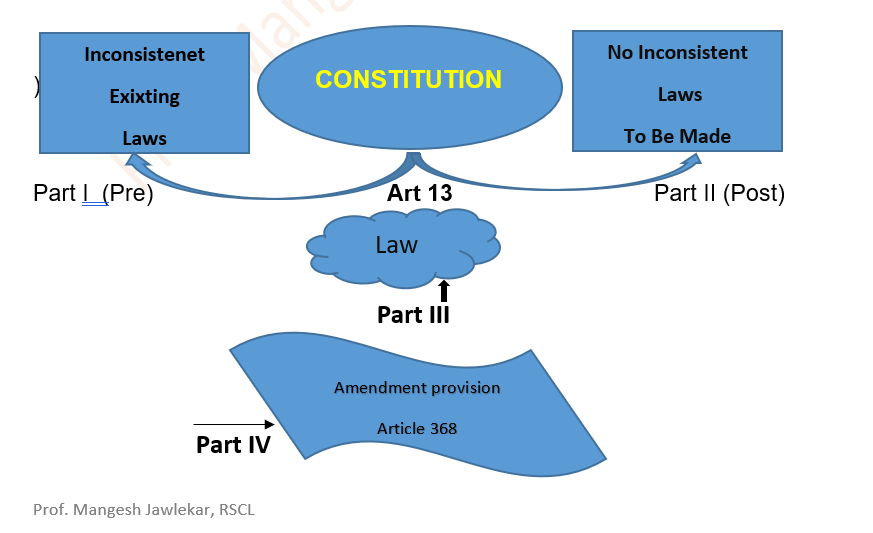

(1) All laws in force in the territory of India immediately before the commencement of this Constitution, in so far as they are inconsistent with the provisions of this Part, shall, to the extent of such inconsistency, be void.

(2) The State shall not make any law which takes away or abridges the rights conferred by this Part and any law made in contravention of this clause shall, to the extent of the contravention, be void.

(3) In this article, unless the context otherwise requires.-

“law” includes any Ordinance, order, bye-law, rule, regulation, notification, custom or usages having in the territory of India the force of law;

“laws in force” includes laws passed or made by Legislature or other competent authority in the territory of India before the commencement of this Constitution and not previously repealed, notwithstanding that any such law or any part thereof may not be then in operation either at all or in particular areas.

(4) Nothing in this article shall apply to any amendment of this Constitution made under Article 368.

‘People believe in law’ and to keep that belief, the Drafting committee gave the concept of Fundamental Rights in Part III of the Indian constitution. It gives liberty to the citizens of India and protects it from being infringed by the state. It also provides for the remedy if their fundamental right is violated.

And to keep the belief of people in the State, Article 12 and 13 were introduced. Article 12 gives the definition of state and tells about the responsibility the state has towards people and their fundamental rights whereas Article 13 of the Indian constitution which presents itself in four parts, makes the concept of fundamental rights more powerful and gives it a real effect.

Article 13 in fact provides for the ‘judicial review’ of all legislations in India, past as well as future. The power has been conferred on the High Courts and Supreme Courts of India (under article 226 and art 32 respectively) which can declare a law unconstitutional if it is inconsistent with any of the provisions of part-III of the Constitution.

‘Judicial Review’ is the power of courts to pronounce upon the Constitutionality of legislative acts which fall within their normal jurisdiction to enforce and power to refuse to enforce such as they find to be unconstitutional and hence void.

Judicial review is the power of the Supreme Court and the High Courts to examine the constitutionality of the Acts of the Parliament and the state legislatures and executive orders both of the centre and state governments. If it is found that any of its provisions are in violation of the provisions of the constitution, they can be declared unconstitutional or ultra-vires of the constitution and a law declared by the Supreme Court as unconstitutional cannot be enforced by the government. The judiciary by using this power keeps the legislative and the executive organs within the purview of the constitution.

Objective of ‘Judicial Review can be summarized as :

i. To uphold the principle of the supremacy of the Constitution.

ii. To maintain balance between the centre and the states.

iii. To protect the fundamental rights of the citizens.

Fundamental rights do exists from the date on which The Indian Constitution came into existence i.e. from 26th Jan 1950. Hence became operative from this date only.

Pre-Constitutional Laws : According to clause (1) of Art 13, all pre-Constitution law or existing laws, i.e., laws which were in force immediately before the commencement of Constitution shall be void to the extent to which they are inconsistent with fundamental rights from the date of the commencement of the Constitution.

Article 13 not retrospective in effect : Article 13(1) is prospective in nature. All pre-Constitution laws inconsistent with fundamental rights will become void only after the commencement of the Constitution. They are not void ab initio. “ Such inconsistent law is not wiped out so far as the past Acts are concerned.

Keshava Madhav Menon v. State of Bombay

The SC observed that, there is no fundamental right that a person shall not be prosecuted and punished for an offence committed before the Constitution came into force. So far as the past Acts are concerned the law exists notwithstanding that it does not exist with respect to the future exercise of the Fundamental Rights.

In that case, a prosecution proceeding was started against the petitioner under the Press (Emergency Powers) Act, 1931 in respect of a pamphlate published in 1949. The present Constitution came into force during the pendency of the proceeding in the Court. The appellant contended that the Act was inconsistent with the fundamental rights conferred by Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution hence void, and the proceeding against him could not be continued. The SC held that Article 13(1), could not apply to his case as the offence was committed before the present Constitution came into force and therefore, the proceedings started against him in 1949 were not affected.

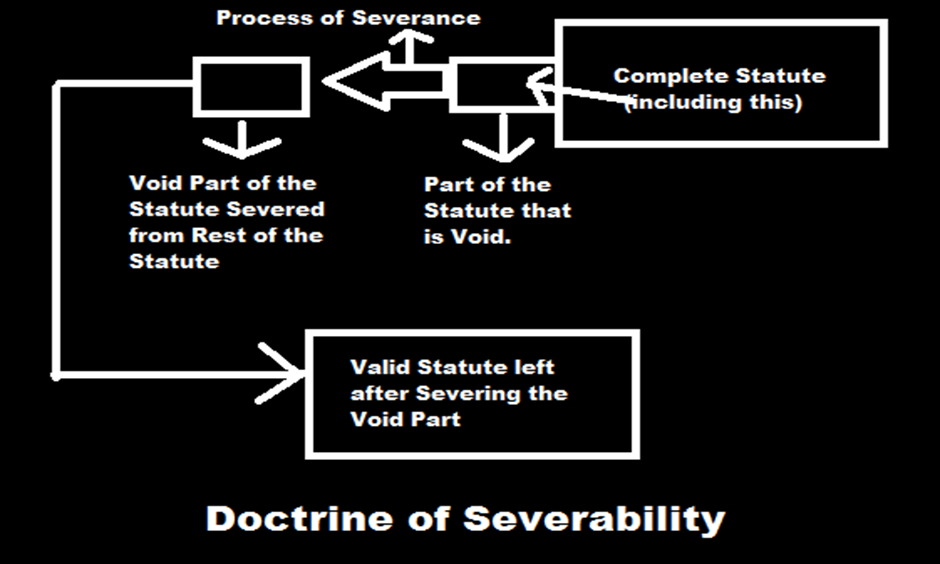

Doctrine of Severability

When a part of the statute is declared unconstitutional then a question arises whether the whole of the statute is to be declared void or only that part which is unconstitutional should be declared as such. To resolve this problem, the SC has devised the doctrine of severability or separability.

The doctrine of severability means that when some particular provision of a statute offends (violates) or is against a constitutional limitation, but that provision is severable from the rest of the statute, only that offending provision will be declared void by the Court and not the entire statute.

This, is, however, subject to one exception. If the valid portion is so closely mixed up with invalid portion that it cannot be separated, then the courts will hold the entire Act, void.

The doctrine of severability was elaborately considered by the supreme court of India in the case of R.M.D.C vs Union of India and the rules regarding severability was laid down in this case-

- The intention of the legislature behind this is to determine whether the invalid portion of the statute can be severed from the valid part or not.

- And if it happens that both, the valid and invalid parts can’t be separated from each other then the invalidity of the portion of the statute will result in invalidity of the whole act.

In A.K. Gopalan v. State of Madras, the SC while declaring section 14 of the Preventive Detention Act,1950, as ultra vires, observed that, “The impugned Act minus this section can remain unaffected. The omission of the section will not change the nature or the structure of the legislation. Therefore, the decision that section 14 is ultra vires does not affect the validity of the rest of the Act.”.

Similarly, in State of Bombay v. F.N. Balsara, a case under Bombay Prohibition Act, 1949, it was observed that the provisions which have been declared as void do not affect the entire statute, therefore, there is no necessity for declaring the statute as invalid.

Doctrine of Eclipse

The Doctrine of Eclipse is based on the Principle that a law which violates Fundamental Rights is not nullity or void ab initio but

becomes only unenforceable. It is Overshadowed by the Fundamental Rights and remains dormant, but it is not dead.

• According to Article 13(1) of the Indian Constitution, all laws in force in the territory of India immediately before the commencement of this Constitution, in so far as they are inconsistent with the provisions of this Part, shall, to the extent of such inconsistency, be void.

• Such laws are not dead, they remain inactive they are in dormant state, not wiped out entirely from the statute book.

• They come alive if the restrictions posed by the fundamental rights of the constitution are removed. Also, such eclipsed laws are operative for cases that arose before the commencement of the Constitution. Hence, the Current Fundamental Rights eclipse the Contravening part of those laws, rendering(providing) that part of the law as dormant.

Deep Chand Vs State of Uttar Pradesh (1959) :

In this case, the supreme court held that a post-constitutional law made under article 13 (2) which contravenes a fundamental right is nullity from its Inception and a stillborn law. It is void ab initio. The doctrine of eclipse does not apply to post-constitutional laws and therefore, a subsequent Constitutional Amendment cannot revive it. The Doctrine of eclipse applies only to pre-constitutional law and not post-constitutional law. Again in 1963, in Mahendra Lal Jain v. State of UP, the SC approved this majority view of Deep Chand’s case and held that the doctrine of eclips applies only to pre-

constitutional law.

But in State of Gujarat v. Ambica Mills (1974), the SC modified its view expressed in Deep Chand and Mahendra Lal Jains’s cases and held that, a post Constitutional law which is inconsistent with fundamental rights is not nullity or non-existent in all cases and for all purposes. A post-Constitutional law which takes away or abridges the right conferred by Article 19 will be operative as regards to non-citizens because fundamental rights are not available to non-citizens.

Keshavan Madhava Menon v. State of Bombay

The question were as to whether a prosecution commenced under section 18, Indian Press(Emergency Powers) Act, 1931, before the coming into existence of the Constitution, could be continued even after the presence of Article 13(1) in the Constitution and whether the Act violated Article 19(1)(a) and (2). The SC by majority, held that the prosecution would continue because the Constitution could not be given a retrospective operation in the absence of an express or necessary implied provision to that effect nor was there anything to that effect in Article 13(1) of the Constitution.

It is also stated that, such laws which are overshadowed, are not wiped out entirely from the statute book. They exist for all past transaction, and for the enforcement of rights acquired and liabilities incurred before the present Constitution came into force and for determination of right of persons who have not been given fundamental rights by the Constitution e.g., non-citizens.

When a Court strikes a part of law, it becomes unenforceable. Hence, an ‘eclipse’ is said to be cast on it. The law just becomes invalid but continues to exist. The eclipse is removed when another (probably a higher level court) makes the law valid again or an amendment is brought to it by way of legislation.

The Supreme Court of India, in P Ratinam case ( P. Rathinam v. UOI, 1994) has held Section 309 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 (attempt to commit suicide) unconstitutional. (‘The right to live’ under Article 21 includes the ‘Right not to live’, i.e. right to die.)

Hence, the section was under eclipse.

However, a constitutional bench in Gian Kaur case (Gian Kaur v. State of Punjab, 1996) reversed this decision and held the section as constitutional whereby the eclipse was removed and it became operable again. (The “right to die” is inconsistent with the “right to life”.)

Post-Constitution Laws :- Clause (2) of Article 13 prohibits State to make any law which takes away or abridges rights conferred by Part-III of the Constitution. If State makes such a law then it will be ultra vires and void to the extent of the contravention.

Though post-Constitution laws inconsistent with fundamental rights are void from their very inception yet a declaration by a Court of their invalidity will be necessary. (Md. Ishaq v. State)

As distinguished from clause (1), clause (2) makes the inconsistent laws void ab initio and even conviction made under such unconstitutional laws shall have to be set aside.

Does the doctrine of eclips apply to a post-constitutional law ?

Deep Chand v. State of U.P. : The doctrine of eclips does not apply to post-Constitutional laws.

Mahendra Lal Jain v. State of U.P., the SC approved the view expressed in Deep Chand’s case and held that the doctrine of eclips applies only to pre-Constitution law under Art. 13(1) and not to post Constitution law under Art. 13(2).

But in State of Gujrat v. Ambika Mills, the SC modified it view as expressed in Deep Chand and Mahendra Lal Jain’s cases and held that a post-Constitution law which is inconsistent with fundamental rights in not nullity or non-existent in all cases and for all purposes. It will be operative as regards to non-citizens because fundamental rights are not available to non-citizens. Such a law will become void or non-existent only against citizens because fundamental rights are conferred on them.

Clause 3 : This clause defines what is ‘Law’ and ‘Laws in force’.

The definition of ‘law’ in this Article is wider than the ordinary connotation of law which refers to enacted law or legislation. It is defined as including an Ordinance, Order, bye-law, regulation, notification, custom or usage having the force of law.

It includes even the administrative order issued by an executive officer, but does not include administrative direction or instructions issued by the Government for the guidance of its officers. It does not include departmental instructions.

Order :- It is a statement/notice issued by concerned authority. It mean you have to obey or your compliance is necessary.

Ordinance :- A law, decree, or statute. Ordinance promulgated by the President of India under Art 123, or the Governer of any State under Art 213, when the legislature is not in session.

Bye-Laws :- A rule of administrative provision which is adopted by an association or corporation for its internal governance.

Regulation :- Rule prescribed for the management of some matter; rule or order having the force of law issued by an executive authority of a government usually under power granted by the Constitution. (section 3(50) the General Clauses Act.)

Notification : A written or printed matter that gives notice ; Formal declaration, proclamation(public notice), and publication of an order either generally or in the manner prescribed.

Custom is a law not written, established long usage, and consent of the ancestors & Usage is that, which has by long continuance acquired a legally binding force.

‘Law in force’ denote all prior and existing laws passed by the competent authority which have not been repealed notwithstanding the fact that are not in operation wholly or in part throughout India or part thereof.

The term ‘having the force of law’ means rule of conduct should be called a law. It must be established that it has a force of law.

Clause 4 : Nothing in this article shall apply to any amendment of this Constitution made under Article 368.

The question whether the word ‘law’ in clause(2) of Article 13 also includes a ‘Constitutional amendment’ was first time considered by the SC in Shankari Prasad v. Union of India (1951).

In this case, the Constitutional validity of the 1st Amendment Act (1951) which curtailed the right to property was challenged.

The Court held that, the word ‘law’ in clause 2 did not include law made by Parliament under Art 368. The word ‘law’ in Art 13 must be taken to mean rules and regulations made in exercise of ordinary legislative power and not amendments to the Constitution made in exercise of Constitutional power and, therefore, Art 13(2) did not affect amendments made under Article 368.

This interpretation of Shankari Prasad’s case was followed by the majority in Sajjan Singh v. State of Rajasthan (1965).

But in I.C. Golaknath v. State of Punjab (1967), the SC overruled its decision in the aforesaid cases, and held that the word ‘law’ in Art 13(2) included every branch of law, statutory, Constitutional, etc., and hence, if an amendment to the Constitution took away or abridged fundamental right of citizens, the amendment would be declared void.

In order to remove the difficulty created by the Supreme Court’s decision in Golak Nath’s case, the Constitution (24th Amendment) Act, 1971 was enacted. By this amendment a new clause (4) was added to Article 13, which makes it clear that, Constitutional amendments passed under Art 368 shall not be considered as ‘law’ within the meaning of Art 13 and, therefore, cannot be challenged as infringing the provisions of Part III of the Constitution.

But again in Kesavananda Bharti v. State of Kerala (1973), the Constitutional validity of the Constitution (24th Amendment) Act, 1971 was considered by the SC. The Court overruled the Golaknath case and upheld the validity of the Constitution (24th Amendment) Act, 1971. But at the same time laid down a new ‘doctrine of basic structure’, held that, constituent power under Art 368 does not enable it to alter the basic structure. This means that Parliament cannot abridge or take away fundamental right that forms a part of the basic structure.

Parliament reacted to this doctrine by enacting 42nd Amendment 1976 which amended Art 368 & declared that there is no limitation on Constituent power. No amendment can be questioned in any court including that of the contravention of any of the fundamental right.

Minerva Mills v. UOI (1980) : The SC invalidated this provision as it excluded judicial review which is the basic feature of Constitution. Constitution had conferred limited amending power on the Parliament & Parliament cannot enlarge it to absolute power.

In other words, Parliament can not expand its amending power which will destroy basic feature…limited power cannot be converted to unlimited.

Waman Rao v. UOI (1981) : The SC adhered to the doctrine of basic feature and clarified that, it would apply to amendments enacted after 24th April 1973 i.e. the date of judgment of Kesavanand Bharti’s case