Right to Equality (Article 14 to 18) – Constitutional Law Notes – Law Tribune

Introduction

Article 14 of the Indian Constitution guarantees the right to equality to every citizen of India as well as non-citizens. Article 14 is a general principle relating to equality and Arts. 15, 16, 17, and 18 lay down the specific application to the general rule laid down in Art. 14. Under the scheme of equality, Art. 14 is significant and judiciary has also developed it in many of cases. Equality is one of the magnificent corner-stones of Indian democracy.

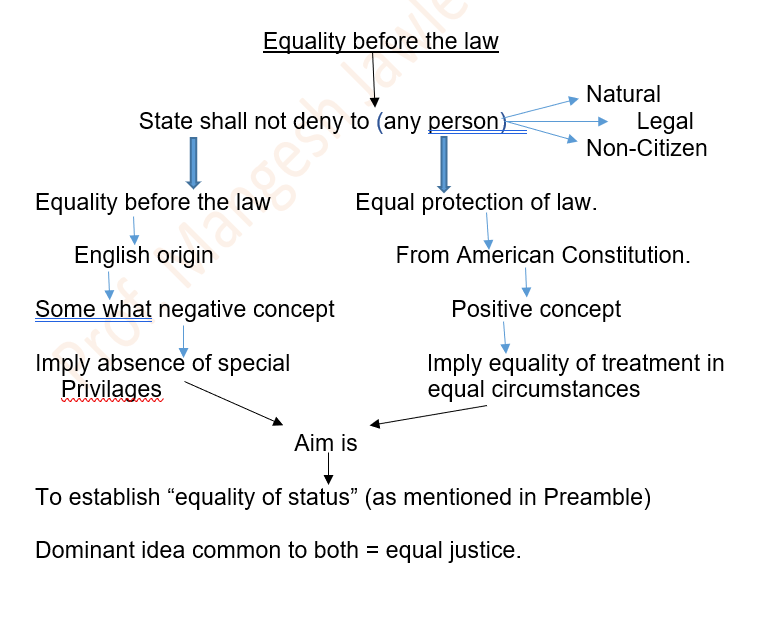

(Article 14 ) Equality before law :-

The State shall not deny to any person

- equality before the law or,

- the equal protection of the laws

…….within the territory of India.

In Indira Nehru Gandhi v. Raj Narayan, the Supreme Court held that,

“the rule of law” embodied in Article 14 is the “basic feature” of the Indian Constitution and hence it cannot be destroyed even by an amendment of the Constitution under Article 368 of the Constitution.

Question :- What is Rule of Law ?

Answer :- It means that no man is above the law and that every person, whatever be his rank or condition, is subject to the jurisdiction of ordinary courts. The rule of law imposes a duty upon the state to take special measure to prevent and punish brutality by police methodology. The rule of law embodied in article 14 is the ‘basic feature’ of the Indian Constitution and cannot be destroyed even by an amendment under article 368.

Rubinder Singh v. UOI : Rule of law requires that, no person shall be subjected to harsh, uncivilised or discriminatory treatment even when the object is the securing of the paramount exigencies of law and order.

As per Professor Dicey, The guarantee f equality before law is an aspect of the ‘rule of law’. Every person, whatever may be the rank, is subject to ordinary courts. As per Prof. Dicey, Rule of Law means,

- Absence of ‘Arbitrary power’ or ‘Supremacy of the law’. It means the absolute supremacy of law as opposed to the arbitrary power of the Government

- Equality before law. It means subjection of all classes to the ordinary law of the land administered by ordinary law courts. No one is above the law.

In Ashutosh Gupta v. State of Rajasthan, the Supreme Court said that, there is close nexus between equality before law and rule of law. The doctrine of equality before law is a necessary corollary (ओघाने आलेला नैसर्गिक परिणाम/ स्वाभाविक परिणाम) of rule of law which pervades (व्यापणे) the Indian Constitution.

Equality before law :

It is a negative concept which ensures that there is no special privilege in favour of any one that all are equally subject to the ordinary law of the land, and that no person, whatever be his rank or condition, is above the law. This is equivalent to the DICEAN concept of “Rule of law” in Britain. According to him, “With us every official, from the Prime Minister down to a constable is under the same responsibility for every act done without legal justification as any other citizen”.

In Kalyan Sarkar v. Rajesh Rajan , the Supreme Court ruled that, members of Parliament or influential politicians were not above the law and while in custody were to be kept in a prison, cell like any other normal prisoner.

The rule of ‘equality before law’ is however not absolute one and there are number of exceptions to it. i.e., a foreign diplomat enjoys immunity from the country’s judicial process. Article 361 has extended immunity to the President of India and the State Governors from the jurisdiction of the Courts.

Dr. Jennings : Equality before law means that, among equals, the law should be equal and should be equally administered, that like should be treated alike.

(Like is used when one person, or one set of persons, or any ONE entity, is being compared to someone or something. Alike is used when two or more persons or things are being compared to one another. eg. John and Peter are brothers. John is a lot like Peter. John and Peter are alike.)

Equal protection of law :-

It is a positive concept which ensures that, all persons have the right to equal treatment in similar circumstances, both in the privilege conferred and in the liabilities imposed by laws. It emphasizes that equal laws should be applied to all in the same situation and that there should be no discrimination between one person and another. Thus it means that, equals can be treated equally, but unequals cannot be treated equally. Because of this a law in question based on reasonable classification is not regarded as discrimination.

In State of West Bengal v. Anwar Ali Sarkar, Court held that, the concept of, “ equal protection of law” is corollary of the, “equality before law” and it is difficult to imagine a situation in which the violation of the equal protection of law will not be the violation of the equality before law. Both the expressions means one and the same thing that is equal justice.

Dr. V.N.Shukla (Author) in his book says that, the like should be trated alike and not that unlike should be treated alike.

The words ‘any person’ in Art 14 means equality before the law is guaranteed to all without regard to race, colour, or nationality. Corporation being juristic persons are also entitled to the benefit of Art 14. (Chiranjit Lal V. UOI)

Raghubir Singh v. State of Haryana : The rule of law imposes a duty upon the state to take special measure to prevent and punish brutality by police methodology.

Exceptions to the Rule of Law :

- Equality before law does not mean the “powers of the private citizens are the same as the power of public officials.

- The rule of law does not prevent certain classes of persons being subject to special rules. Thus members of armed forces are controlled by military laws.

- Today ministers and other executive bodies are given very wide discretionary powers by statute. A large number of legislation is passed in the form of ‘delegated legislation’.

- Certain members of society are governed by special rules in their professions eg doctors, lawyers.

Article 14 permits classification but prohibits class legislation :

The equal protection guaranteed by Art 14 does not mean that all laws must be general in character.

It does not means that the same laws should apply to all persons.

The varying needs of different classes of persons often require separate treatment. Identicle treatment in unequal circumstances would amount to inequality. So a reasonable classification is not only permitted but is necessary if society is to progress.

The classification, however, must not be arbitrary.

Art 14 applies where equals are treated differently without any reasonable basis. But where equals and unequals are treated differently, Art 14 does not apply.

‘Class legislation’ is that which makes an improper discrimination by conferring particular privileges upon a class of persons arbitrarily selected from a large numbers of persons, all of whom who stand in the same relation.

Test of reasonable classification :

Article 14 permits reasonable classification by the legislature for the purpose of achieving specific ends. Classification to be reasonable should fulfil, the following two tests.

(1) The classification must be based on an intelligible(समजण्यास सोप्पा / स्पष्ट ) differentia(भिन्नता) which distinguishes persons or things that are grouped together from others left out of the group; and

(2) The differentia must have some rational relation to the object sought to be achieved by the Act.

What is necessary here is that, there must be substantial basis for making the classification. There should be a nexus between the basis of classification and the object of the Statute under consideration. In other words there must be some rational nexus between the basis of classification and the object intended to be achieved.

Supreme Court of India in a number of cases has established certain important principles by which nature and scope of reasonable classification can be properly understood. The propositions laid down in ‘Dalmia’s case’ holds good governing a valid classification.

A law may be Constitutional even though it relates to a single individual if on account of special circumstances or reasons applicable to him and not applicable to others, that single individual may be treated as a class by itself. (Ram Krishna Dalmia v. Justice Tendolkar).

There is always a presumption in favour of the Constitutionality of an enactment and the burden is upon him who attacks it to show that there has been a clear transgression of the Constitutional principles. (P.U.C.L. v. Union of India).

The presumption may be rebutted in certain cases by showing that there is no classification.

It must be presumed that the legislature understands and correctly appreciates the need of its own people.

The classification made by the legislature need not be scientifically perfect or logically complete. (Kedar Nath v. State of W.B.).

The question whether a classification is reasonable, and proper or not, must however, be judged more on commonsense than on legal subtleties(सूक्ष्मता).

The classification may be made on different basis, e.g. geographical, according to the objects, or occupation or the like.

Classification based on geographical basis :

The words, “within the territory of India” used under Article 14 does not mean that there must be a uniform law throughout the country. A law may be applicable to one State and not the other. A classification may be, therefore, properly made on geographical basis.

In M.P. Oil Extraction and Fur v. State of M.P., the Supreme Court held that a favored treatment to those situated in backward and tribal areas cannot be held to be illegal and arbitrary.

Classification in favour of State :

The term “person” in Article 14 does not include “State”. Therefore, a classification which treats the State, differently from persons, may not be violative of the rule of equal protection of law.

In Sagir Ahmed v. State of U.P., a monopoly created by the State in its favour with reference to business of Motor Transport was held valid as not offending Article 14.

Special Courts and special procedure :

Parliament of India is empowered to set up special Courts and to provide special procedure for the trial of certain ‘offences’ or ‘classes of offences’. Such a law is not violative of Article 14, if it lays down proper guidelines for ‘classifying the offences’ or ‘classes of cases’ to be tried by the special Court.

In Basheer v. State of Kerala, the Supreme Court upheld the

classification between cases pending before the Court and under investigation on the date of commencement of the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (Amendment)Act, 2001 and the cases pending in appeal. The amendment was brought with the object of avoidance of delay in trials.

New Concept of Equality :

Since early 1970 equality under Article 14 has acquired new and important dimensions. The new concept of equality that is protection against arbitrariness has been evolved by the Supreme Court of India. According to it, if the action of the State is arbitrary then it cannot be justified even on the basis of doctrine of reasonable classification. Every act of the executive which is arbitrary is unequal and is violative of Article 14.

State of Bihar v. Bihar 10+2 Lecturers Associations (2007) :

Education can be basis of classification. It has been held that, there is a clear distinction between a trained teacher and untrained teacher. Such a distinction is valid, rational and reasonable. Prescribing different pay scales cannot be held illegal, improper or unreasonable infringing Art. 14 of the Constitution. Art 14 forbids discrimination not classification.

In D.S. Nakara v. UOI (1983), the SC struck down the rule 34 of the Central Services (Pension) Rules, 1972 as unconstitutional on the ground that, the classification made by it between pensioners retiring before a particular date and retiring after that day was not based on any rational principle and was arbitrary and violative of Art 14 of the Constitution.

Central Inland Water Transport Corpn. Ltd. v. Brojo Nath (1986) :

Rule of Natural Justice implicit in Article 14 : The SC has held that, Service Rules empowering the Government Corporation to terminate Services of permanent employees without giving reasons on three months notice or pay in lieu of notice period is violative of Art 14 being unconscionable, arbitrary, unreasonable and against public policy as it wholly ignores the audi alteram partem rule. The service rule confers an absolute, arbitrary aand unguided power to terminate services of its employees without giving any reasons.

In E.P Royappa v. State of T.N., (1978), the Supreme Court rejected the traditional concept of equality based on the doctrine of reasonable classification and laid down new concept of equality.

Supreme Court said that if the action of the State is arbitrary then it

cannot be justified even on the basis of reasonable classification.

In the famous case Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India, (1978), Supreme Court said that, Article 14 strikes at arbitrariness in State action and ensures fairness and equality of treatment. So what is arbitrary is unequal and is violative to Article 14 of the Constitution.

Again in Air India v. Nargesh Meerza, (1981) : Supreme Court struck down the Regulation providing for retirement of the Air Hostess on her first pregnancy, as arbitrary and unreasonable and hence violative under Article 14 of the Constitution.

Randhir Singh v. UOI (1982) : Equal pay for equal work :

The SC has held that, although the principle of ‘equal pay for equal work’ is not expressly declared by our Constitution to be a fundamental right but it is certainly a constitutional goal under Art 14,16 & 39(c) of the Constitution. This right can, therefore, be enforced in cases of unequal scales of pay based on irrational classification.

Summary :

**Equality before law = Absence of discrimination.

**Equal protection of law = Equal treatment in equal circumstances

**To attain equity, reasonable classification is permitted.

**Reasonable classification should not amount to class legislation.

Application to the general rule of Equality

Articles 15 and 16 of the Constitution has laid down specific application to the general rule of equality as mentioned in article 14.

Article 15 is much wider than Article 16. However both these Articles

can be invoked by citizens only.

NO DISCRIMINATION ON GROUNDS OF RELIGION, RACE, CASTE, ETC.

(Article 15) 1. Prohibition of discrimination against citizens (Article 15)

The Constitutional mandate of Article 15 speaks about equal justice without any discrimination on the ground of race, religion, caste etc. It can be discussed as under.

(1) Clause (1) prohibits the State from discriminating against citizens on grounds only of religion, race, sex, caste, place of birth or any of them.

The word ‘discrimination’ means to make an adverse distinction or to distinguish unfavourable from others. If a law makes discrimination on any of the above grounds it can be declared invalid.

In D.P. Joshi v. State of M.B., it was held that a law which discriminates on the ground of residence does not violate Art 15(1). What Art 15(1) prohibits is discrimination based on place of birth. Place of birth and residence are different.

The word ‘only’ used in Art 15(1) indicates that, discrimination cannot be made merely on the ground that one belongs to a particular caste, sex, etc. In other words, if other qualifications are equal, caste, religion, etc, should not be a ground for preference or disability.

(2) Clause (2) provides that no citizen shall, on the ground only of religion, race, caste, sex, place of birth, be subject to any disability, liability restriction or condition with regard to-

(a) access to shops, public restaurants, hotels and places of public entertainment, or

(b) the use of wells, tanks, bathing ghats, roads and places of public resort, maintained wholly or partly out of State funds or dedicated to the use of general public.

Art 15(2) is a specific application of the general prohibition contained in Art 15(1). ‘Place of public resorts’ means places which are frequented by the public like a public park, a public road, public bus/railway/hospital etc

It is to be noted that, while clause (1) prohibits discrimination by the State, clause (2) prohibits both, the State and private individuals from making any discrimination.

(3) Clause (3) enacts that nothing in Article 15 shall prevent the State from making any special provision for women and children.

Clause (3) is one of the two exception to the general rule laid down in Clause (1) & (2) of Art 15. As women & children are most vulnerable group in the society because of their physical structure, and place them at a disadvantage in the subsistence, it allows the State to make special provisions for women & children and it would not be violation of Art 15.

(4) Clause (4) provided that nothing shall prevent the State from making any special provision for the advancement of any socially and educationally backward classes and for the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes.

Clause (4) was added by the Constitution (First Amendment) Act, 1951 as a result of the decision of the Supreme Court in State of Madras v. Champakam Dorairajan, (1950).

In that case the Madras Government had reserved seats in State Medical & Engineering College for different communities in certain proportions on the basis of religion, race & cast. The State defended the law on the ground that, it was enacted with a view to promote the social justice for all sections of the people as required by Art 46 of the Directive Principles of State Policy. (Art 46. Promotion of educational and economic interests of Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and other weaker sections The State shall promote with special care the educational and economic interests of the weaker sections of the people, and, in particular, of the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes, and shall protect them from social injustice and all forms of exploitation). The SC held that law void because it classified students on the basis of caste and religion irrespective of merit. The Directive Principles cannot override the Fundamental rights.

To modify the effect of this decision, Art 15 was amended and clause (4) was added.

The provisions made in clause (4) of Art 15 is only an enabling provision and does not impose any obligation on the State to take any special action under it. It merely confers a discretion to act if necessary by making special provisions for backward classes. (Balaji v. St of Mysore)

Art 15(4) is not an exception but only makes a special application of the principle of reasonable classification. (G. Prakash V. St of Haryana).

The class contemplated under the clause must be both socially and educationally backward.

What are Backward Classes is not defined in the Constitution. Art 340, however, empowers the President to appoint a commission to investigate conditions of socially and educationally backward classes.

Art 341 is related to Scheduled casts & Art 342 is related to Scheduled Tribes. The Court can consider whether the classification made by the Government is arbitrary or is based on any intelligible and tangible principle.

Balaji v. State of Mysore (1963) : The Mysore Government issued an order Under Art 15(4) reserving seats in Medical & Engineering Colleges in the State as follows

Backward Classes : 28 % More Backwards Classes : 22%

Scheduled Caste : 15 % Scheduled Tribes : 3%

Total : 68 %

Only 32 % was available for merit pool.

This Government order was challenged in this case.

The Supreme Court while Striking out this reservation of 68%, held that,

While determining backward class, the backwardness must be considered on both social and educational background only social or only educational should not be considered. Caste cannot be sole dominant test. Poverty, occupation place of habitation or any other relevant factors should also be taken into consideration. The impugned order, however, proceeds only on the basis of castes only without regards to other relevant factors and that is sufficient to render the order invalid.

It was also held by the Court for the first time that, the reservation should be less than 50 %. Further the Court also held that, classification of backward class and more backward class is not valid.

But if entire caste is found to be socially and educationally backward, then it may be included in the list of BC.

But in Indra Sawney v. Union of India (1993), popularly known as Mandal Commission case, it was held that, Backward class of citizens can be identified on the basis of caste and not only on economic basis.

Distinction between backwards class and more backward class was also held to be valid.

(5) Nothing in this article or in sub-clause (g) of clause (1) of article 19 shall prevent the State from making any special provision, by law, for the advancement of any socially and educationally backward classes of citizens or for the Scheduled Castes or the Scheduled Tribes in so far as such special provisions relate to their admission to educational institutions including private educational institutions, whether aided or unaided by the State, other than the minority educational institutions referred to in clause (1) of article 30.

Art 15(5) was inserted by the Constitution (93rd Amendment) Act, 2005. (with effect from 20/1/2006) with the object of Greater access to higher education including professional education to a larger number of students belonging to the socially and educationally backward classes of citizens or for the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes & to promote the educational advancement of the socially and educationally backward classes of citizens or of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes in matters of admission of students belonging to these categories in unaided educational institutions, other than the minority educational institutions referred to in clause (1) of article 30 of the Constitution

This amendmend enables the State to make provision for reservation for the above categories of classes in admission to private educational institutes. The amendment, however, keep the minority educational institutions out of its purview.

In Indian Medical Association v. UOI, the Supreme Court held the provisions of clause (5) of Art 15 not violative of Art 32 & 226 as it does not take away the power of judicial review and also not violative of basic structure of the Constitution.

(Article 16) Equality of opportunity in matters of public employment :-

(1) There shall be equality of opportunity for all citizens in matters relating to employment or appointment to any office under the State.

(2) No citizen shall, on grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex, descent, place of birth, residence or any of them, be ineligible for, or discriminated against in respect of, any employment or office under the State.

(3) Nothing in this article shall prevent Parliament from making any law prescribing, in regard to a class or classes of employment or appointment to an office under the Government of, or any local or other authority within, a State or Union territory, any requirement as to residence within that State or Union territory prior to such employment or appointment.

(4) Nothing in this article shall prevent the State from making any provision for the reservation of appointments or posts in favour of any backward class of citizens which, in the opinion of the State, is not adequately represented in the services under the State.

(4A) Nothing in this article shall prevent the State from making any provision for reservation in matters of promotion, with consequential seniority, to any class or classes of posts in the services under the State in favour of the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes which, in the opinion of the State, are not adequately represented in the services under the State.

(4B) Nothing in this article shall prevent the State from considering any unfilled vacancies of a year which are reserved for being filled up in that year in accordance with any provision for reservation made under clause (4) or clause (4A) as a separate class of vacancies to be filled up in any succeeding year or years and such class of vacancies shall not be considered together with the vacancies of the year in which they are being filled up for determining the ceiling of fifty per cent. reservation on total number of vacancies of that year.

(5)Nothing in this article shall affect the operation of any law which provides that the incumbent of an office in connection with the affairs of any religious or denominational institution or any member of the governing body thereof shall be a person professing a particular religion or belonging to a particular denominat.

Art 14 : Discuss equality in widest term

(Equality before law + Equal protection of law.)

Art 15 : Protects equality but prohibits

discrimination on 5 grounds (r r c s pb)

Art 16 : Limited to employment and appointment

On 7 grounds (r r c s pb+descent+residence)

While Constitutional debates on Art 16, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar

called reservations as Compensatory Benefits. He said some sections of society are such that they have been discriminated for a quite long time and in order to establish a welfare society, it is necessary the upliftment of these sections. He said the actual meaning of equality is to remove disabilities and create new opportunities.

Equality = (-) Remove disabilities & (+) Create new opportunities.

Art 16 : Equality of opportunity in matters of public employment :

Another particular application of the general principles of equality as mentioned in Art 14 is contained in Art 16. It can be read as under :

(1) In clause (1) the general rule is laid down that there shall be equal opportunity for citizens in matters relating to ‘employment’ or ‘appointment to any office’ under the State.

(2) Clause (2) lays down specific grounds on the basis of which citizens are not to be discriminated against each other in respect of any appointment or office under the State. The prohibited grounds of discrimination are religion, race, caste, sex, descent, place of birth, residence or any of them.

(3) Under clause (3) Parliament is authorized to determine that residence can be a criteria with regards to ‘appointment and ‘employment’ to any office under the State.

(4) Under clause (4) State can provide for the reservation of appointment or posts in favour of any backward class of citizens which in the opinion of the State are not adequately represented in the services of the State.

While Clause (4 –A) speaks about reservation in promotions,

Clause (4-B) speaks about reservation which may exceed 50%

in fulfilling backlog vacancies.

(5) Clause (5) says that appointment to religious institutions or institutions regulating religious instructions may be restricted

to persons of that religion.

Equality and Reservation Policy- Judicial views

As discussed earlier, Article 16 (4) of the Constitution empowers State to make special provision for the reservation of appointment of posts in favour of any backward class of citizens who in the opinion of the State are not adequately represented in the services of the State.

Thus Article 16(4) applies only if two conditions are satisfied.

1. The class of citizens is backward and

2. The said class is not represented in the services of the State.

In Balaji v. State of Mysore, (1963), the Supreme Court held that the caste of a person cannot be the sole test for ascertaining whether a particular class is a backward class or not. Poverty, occupation, place of habitation may all be relevant factors to be taken into consideration. But if the entire caste is backward then it can be included in the list of backward classes. Caste cannot be continued to be backward for all the times. Caste can be deleted from the list of backward if it reaches to the state of progress. Court said that reservation given should be less than 50%.

Again the scope of Article 16(4) was considered by the Supreme

Court in Devadason v. Union of India, (1964).

In this case the validity of ‘carry forward rule’ provided that if sufficient number of candidates belongs to Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes were not available for appointment to the reserved quota, the vacancies that remains unfilled would be treated as unreserved and filled by fresh available candidates. But a corresponding number of posts would be reserved in the next year for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes in addition to their reserved quota of the next year.

The result was that to carry forward the unutilized balance in next year in actual effect 68% of vacancies were reserved for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes.

The Supreme Court by a majority of 4-1 struck down the carry forward rule as unconstitutional. Court held that reservation ought to be less than 50%, but how much less than half would depend upon

prevailing circumstances in each case.

Supreme Court gave a new interpretation to Article 16 of the

Constitution in State of Kerala v. Thomas, (1976).

Kerala Government passed the impugned order granting exemption of two years to Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes candidates to pass the entrance test for the post of division clerk and upper division clerk in the registration department. This exemption was challenged as

discriminatory under Article 16 (1). Supreme Court upheld it as

Constitutional and said that reservation for backward classes may be

made even outside the scope of clause (4) of Article 16.

Further in A.B.S.K. Sangh (Railway) v. Union of India (1981),

The Supreme Court by following Thomas case upheld the validity of the Railway Board Circular under which reservations were made in selection posts of the Schedule Castes and Scheduled Tribes candidates. The Court also upheld the carry forward rule wherein the reservation quota came to about 64.4%.

As a result of the decision of the Supreme Court in Thomas and

A.B.S.K. Sangh case, Balaji and Devdason case have been impliedly

overruled.

Indra Sawhney v. UOI (1993)—The Mandal Case

The scope and extent of Art 16(4) has been examined thoroughly by the Supreme Court in the historic case of Indra Sawhney v. UOI popularly known as the Mandal case. The facts of the case were as follows :

On January 1, 1979 the Government headed by the Prime Minister Shri Morarji Desai appointed the second Backwards Classes Commission under Art 340 of the Constitution under the Chairmanship of Shri B.P. Mandal to investigate the socially and educationally backward classes within the territory of India and recommend steps to be taken for their advancement including desirability for making provisions for reservation of seats for them in Government job.

The Commission submitted its report in Dec 1980. It had identified as many as 3743 cases as socially and educationally backward classes and recommended for reservation of 27% Government jobs for them.

Subsequently, many political changes, policy changes, difference of opinion took place.

The Supreme Court examined the scope and extent of Article 16(4) in detail and clarified in detail various aspects on which there were differences of opinion in various earlier judgments. The majority opinion of the Supreme Court on various aspects of reservation provided in Article 16(4) may be summarized as follows :-

(1) Backward class of citizens in Article 16(4) can be identifiedvon the basis of caste and not only on economic basis. Thevmajority held that a caste can be and quite often is a socialvclass in India and if it is backward socially it would be a backward class for the purposes of Article 16(4).

(2) Article 16(4) is not an exception to Article 16(1). It is an instance of classification. Reservation can be made under Article 16(1) itself. Thus according to Supreme Court reservation can be made under clause (1) on the basis of reasonable classification.

(3) Backward classes in Article 16(4) are not similar to a socially and educationally backward in Article 15(4). It is much wider. Clause (4) does not contain the qualifying words, ‘socially and educationally’ as does clause (4) of Article 15.

(4) Creamy layer must be excluded from backward classes.

(5) Article 16(4) permits classification of backward classes into backward and more backward classes.

(6) A backward class of citizens cannot be identified only and exclusively with reference to economic criteria.

(7) Reservation shall not exceed 50%. Thus according to Court the maximum limit of reservation cannot be more than 50%.

(8) There shall be no reservation in promotions. Reservation is confined only to initial appointments.

(9) The Court directed Union Government and State Government to appoint permanent statutory body to examine complaints of over inclusion / under inclusion.

(10) Reservation can be made by an executive order. It need not be made by Parliament or Legislature.

(11) No opinion was expressed on the correctness or adequacy of the Mandal Commission Report.

(12) Disputes regarding to new criteria can be raised only in the Supreme Court and not before any High Court or Tribunal.

Position after the Mandal Case :

The Court has laid down that there shall be no reservation in promotions in government jobs. But the government has enacted The Constitution (77th Amendment) Act, 1995

By this amendment new clause was added, i.e. clause 4(a), to Article 16 of the Constitution which provides that reservation in promotion in government job will be continued in favour of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes.

The Constitution (85th Amendment) Act, 2001 : This amendment has substituted, in clause 4A, for the words “in matters of promotion to any class” the words “in matters of promotion, with consequential seniority, to any class”.

The Constitution (81ST Amendment) Act, 2000 This Amendment has added a new clause, i.e., clause 4 (b), to Article 16 which provides that in case of fulfilling the backlog vacancies even though reservation exceeds 50% it is Constitutional.

(Article 17) ABOLITION OF UNTOUCHABILITY

Art. 17 :- Abolition of Untouchability : “Untouchability” is abolished and its practice in any form is forbidden The enforcement of any disability arising out of Untouchability shall be an offence punishable in accordance with law.

‘Untouchability’ is neither defined in the Constitution nor in the Act. The Mysore High Court has, however, held that, the term is not to be understood in its literal or grammatical sense but to be understood as the ‘practice as it had developed historically’ in this country.

In exercise of the powers conferred by Art 35, Parliament has enacted ‘The Untouchability (Offences) Act, 1955’.

This Act was amended by ‘The Untouchability (Offences) Amendment Act, 1976’, in order to make the law more stringent to remove untouchability from the society.

It has now been renamed as ‘The Protection of Civil Rights Act, 1955.

The expression ‘Civil Right’ is defined as ‘any right accruing to a person by reason of the abolition of untouchability by Art 17 of the Constitution.

The punishment for the untouchability offenses has been enhanced to a fine as well as imprisonment(6 months) and for further default, the punishment will be extended. For the third and subsequent offenses, the punishment may increase from one-year imprisonment with a fine of Rupees 500 to two years of imprisonment with the fine of Rupees 1000.

One of the important characteristics of this Act is that public servants who willfully show negligence in the investigation of any offense will be punishable under this Act.

It should be noted that Art 15(2) also helps in the eradication of untouchability (access to public places).

In Asiad Project Worker’s case (People’s Union for Democratic Rights v. UOI, 1982), the SC held that the fundamental right under Art 17 are available against private individual and it is the Constitutional duty of the State to take necessary steps to see that, these fundamental rights are not violated.

(Article 18) ABOLITION OF TITLES

Article 18 prohibits the State to confer titles on any body whether a citizen or a non-citizen. Military and academic distinctions are, however, exempted from the prohibition for they are incentives to further efforts in the perfection of the military power so necessary for its existence. & for the scientific endeavours so necessary for its prosparity.

Clause (2) prohibits a citizen of Indian from accepting any title from foreign State.

Clause (3) provides that a foreigner holding any office of profit or trust under the State cannot accept any title from any foreign State without the consent of the President.

Clause (4) provides that, no person holding any office of profit or trust under the State shall, without the consent of the President, accept any present, emolument, or office of any kind from or under any foreign State

Art 18 : Abolition of titles :-

1. No title, not being a military or academic distinction, shall be conferred by the State.

2. No citizen of India shall accept any title from any foreign State.

3. No person who is not a citizen of India shall, while he holds any office of profit or trust under the State, accept without the consent of the President any title from any foreign State.

4. No person holding any office of profit or trust under the State shall, without the consent of the President, accept any present, emolument, or office of any kind from or under any foreign State

The recent conferment of titles (national awards) of “Bharat Ratna”, “Padma Vibhushan”, “Padma Shri”, etc. are not prohibited under Art 18 as they merely denote State recognition of good work by citizens in the various fields of activity. Balaji Raghavan v. UOI (1996), the SC held that the national awards such as “Bharat Ratna”, “Padma Vibhushan”, “Padma Shri” are not violative of principle of equality of the Constitution. The theory of equality does not mandate that merit should not be recognised. The national awards do not amount to titles within the meaning of Art and therefore, not violative. Also Art 51-A(f) speaks of a system of award to recognise excellence in performance of duties.